Meet the researcher - Dr Ben Henley

/Long-term wet-dry phases are largely driven by the distribution of warm water across certain regions of the Pacific Ocean. This phenomenon is referred to as the Inter-decadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) or Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). A broad understanding of these multi-year cycles can help create context and reflect on the timeliness of farm investment, leasing, irrigation water availability, machinery purchases or hiring of personnel. One of Australia’s leading climate researchers in this complex area is Dr Ben Henley of Monash University, Melbourne. His research focuses on climate variability, drought risk, and hydrological impacts using multi-proxy palaeoclimate records observed data and climate model simulations.

Dr Ben Henley

Climate researcher

What inspired you to become a climate researcher and at what age was this?

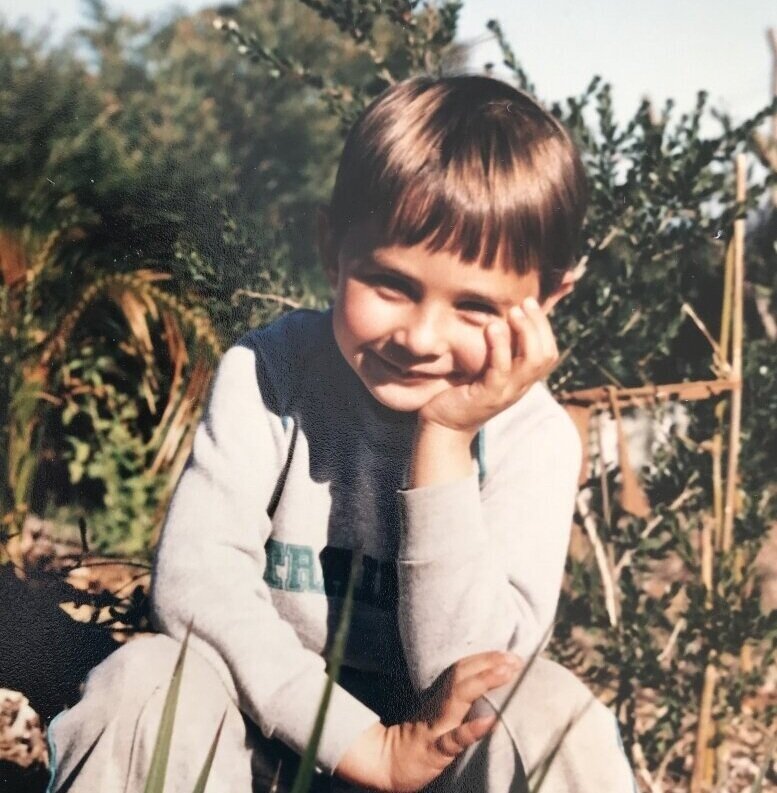

As a small boy, I was fascinated by the natural world. I grew up at the top of a hill in Charlestown, near Newcastle in NSW, surrounded by plants, animals, bush, lake, coast and big skies. From a young age, I watched the weather, the changing seasons and the coal ships from that hill. I came to harbour a sense that we humans can find better ways to live – in support of both human and natural systems – and that this could be achieved through engineering and science. So, I studied Civil and Environmental Engineering. I later combined my mutual love of music and science by studying Acoustics, in Sweden actually. I gathered skills in physics and maths which would end up having some surprising uses in areas of climate and hydrology. I came to understand the scale of the climate change problem after returning from overseas in my early 20s. I read widely on the topic and decided that I simply had to do something to contribute to solving the problem. From then I have been trying to better understand climate change and variability, water resources and how we can best prepare for an uncertain and challenging future.

Do you have any extended family or other connections with farming or agriculture?

I have extended family out near Coonabarabran in NSW, and have great memories visiting their farms as a kid, playing with emu chicks, calves and finding yabbies. My family has always grown our own fruit and vegetables, and my Dad is a passionate gardener of native plants. I hope one day to have a small hobby farm of my own. With a good scientific sense of the variability of the Australian climate, and having such a strong personal connection to the land, I have a deep respect for farming, and the challenges farmers face. I think that is what led me to study drought.

Ben as a youngster, was always fascinated by nature and the environment (Above) and in an interview with ABC newsreader, Ros childs, live on midday tv (RHS).

What are your favourite activities or interests away from research that helps recharge you for work mode?

Music, the outdoors, family and community have always been a huge part of my life. I started playing the piano when I was about 5. I was incredibly lucky that a world-class piano teacher, Ms Rosemary Witcomb, happened to live at the end of my street at the time, and my parents supported my music so deeply. Studying eighth grade classical piano at the same time as year twelve was not easy, but I’ve found that what you put into music, it gives back ten-fold, and at times it is what keeps me going and makes me who I am. I later picked up a couple of other instruments and regularly accompany and harmonise with my wife, who is a professional singer-songwriter, in her choirs and in the general fabric of our day. I loved soccer and cricket as a kid but tend to stick to more individual sports these days. Staying the course through the stresses of academia, like many other professions, demands regular physical and mental escapes including running, bushwalks, yoga, meditation, family, and music.

The “tripole” index, developed by ben is now an internationally recognised method of measuring and assessing long-term cycles of wet and dry in the pacific basin, which has effects across the globe.

What is the simplest, no-nonsense way you can explain the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (PDO)?

The Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation is a climate pattern in the Pacific which varies from decade to decade and affects global and regional climate on 10–40 year timescales. It is like El Niño and La Niña’s older, slower moving, uncle or auntie, I suppose. We have lots of clues as to what drives these slow changes, and how they link to other ocean basins and the El Niño system, as well as how this pattern has behaved in the past, including the impacts on Australia. But our understanding of the underlying physics and potential avenues for predictability of these decade to decade changes remains a matter for ongoing research.

Your 2015 paper with co-author Prof. David Karoly and others has been cited almost 300 times. The tripole index is now published on the NOAA (US) website. What made you curious to take on the task of developing this index for the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation?

The paper arose from a simple recognition, by David and me I recall, that at that point there was no simple and widely-used index to track the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (the IPO). Because the IPO has a signature that extends well beyond the tropics, using an index of El Niño that focusses only on the tropical Pacific would not tell the full story. So, we set about developing our own index. There are of course other ways to track the IPO, which are certainly valid. I am stoked that the index has been useful to many people and that NOAA maintains and updates the index we developed. I learnt through that process, that the most widely used scientific findings are often those which build tools or datasets for others to use.

The rainfall charts produced by the longpaddock.com.au (see image to the right) are fascinating, with clearly defined wet and dry phases that seem broadly aligned with the PDO. It seems more obvious in hindsight, but what are the issues with predicting the next move of this phenomenon?

Reliable predictions of any climate phenomenon rely on a few key things, namely i) a strong understanding of the physical climate mechanisms and the precursors to any shifts; ii) accurate climate model representations, and iii) success in the evaluation of predictions using what is called model hindcast verification. In the case of decade-to-decade changes in the climate, these are very big hurdles! The scientific community has not settled on any one single mechanism for the IPO. We have identified numerous potential drivers and past precursors to the shifts, and there are some excellent theories that need developing and testing. In short: it’s a chaotic system and we need to better observe it, understand it, and model it. I would like to see a concerted global research effort on this topic. I previously proposed a small version of such a project, but alas, my idea narrowly missed out on funding. That’s ok, I’m sure there were other great projects! I think the 10 to 20-year future timeframe is a big challenge, both scientifically, and to those on the land. What happens in the next 10–20 years is critically important for people managing water resources and agricultural systems and it would help a lot to have a clearer insight into that near-term future.

Reconstructing ENSO and other climate drivers using coral cores, tree rings and other measurements over longer-term timescales is also another keen interest area of your research. What are the standout take-home messages you can share that can help us contextualise the horrific 2019 drought and better plan for an extreme period of wet or dry?

Horrific it was. As if the drought was not enough, the intensity and scale of the fires that followed shocked us all. I worked on a paper recently with a large group of scientists led by Nerilie Abram, to put those drought and fire conditions into a longer-term context. The brief message is that we have a highly variable climate and we should expect extremes from year to year, but climate change contributed, and it will continue to throw some massive challenges at us in the coming decades. I’ve used records from corals, tree rings and ice cores to build up multi-century reconstructions of the past, which show that variability is a fundamental feature of our climate but that the rate of global temperature increase is staggering compared to past centuries. Climate change is accelerating, and we must all do all we can to mitigate it and adapt to it, implementing actions locally and adding our voices to the long-term solutions at the global scale. My advice is simple: plan for extremes and take action now. Use the best available evidence to adapt our systems to a variable and changing climate and make rapid structural changes which will contribute to global solutions. Easier said than done, but we must do it.

Click on the short YouTube Below for an explanation of what the Pacific Decadal Oscillation is, how its measured and some impacts.